Difference between revisions of "Contact Materials for Electrical Engineering"

Doduco Admin (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (86 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | The contact parts are important components in switching devices. They have to maintain their function from the new state until the end of the functional life of the devices. | |

| − | The contact parts are important components in switching devices. They have to | ||

| − | maintain their function from the new state until the end of the functional life of the | ||

| − | devices. | ||

| − | The requirements on contacts are rather broad. Besides typical contact properties | + | The requirements on contacts are rather broad. Besides typical contact properties such as |

| − | such as | ||

*High arc erosion resistance | *High arc erosion resistance | ||

| Line 13: | Line 9: | ||

*Good arc extinguishing capability | *Good arc extinguishing capability | ||

| − | + | They have to exhibit physical, mechanical and chemical properties like high electrical and thermal conductivity, high hardness, high corrosion resistance etc. and besides this, should have good mechanical workability and also be suitable for good weld and brazing attachment to contact carriers. In addition they must be made from environmentally friendly materials. | |

| − | and thermal conductivity, high hardness, high corrosion resistance | ||

| − | this should have good mechanical workability | ||

| − | brazing attachment to contact carriers. In addition they must be made from | ||

| − | environmentally friendly materials. | ||

| − | Materials suited for use as electrical contacts can be divided into the following groups | + | Materials suited for use as electrical contacts can be divided into the following groups based on their composition and metallurgical structure: |

| − | based on their composition and metallurgical structure: | ||

*Pure metals | *Pure metals | ||

*Alloys | *Alloys | ||

*Composite materials | *Composite materials | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Pure metals''' | |

| + | |||

| + | Within this group, silver has the greatest importance for switching devices in the higher energy technology. Other precious metals such as gold and platinum are only used in applications for the information technology in the form of thin surface layers. As a nonprecious metal, tungsten is used for some special applications such as, for example, automotive horn contacts. In some rarer cases, pure copper is used, but mainly paired to a silver-based contact material. | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Alloys''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides these few pure metals, a larger number of alloy materials made by melt technology are available for the use as contacts. An alloy is characterized by the fact, that its components are completely or partially soluble in each other in the solid state. Phase diagrams for multiple metal compositions show the number and type of the crystal structure as a function of the temperature and composition of the alloying components. | ||

| − | + | They indicate the boundaries of liquid and solid phases and define the parameters of solidification. | |

| − | + | Alloying allows to improve the properties of one material at the cost of changing them for the second material. As an example, the hardness of a base metal may be increased while at the same time the electrical conductivity decreases with even small additions of the second alloying component. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Composite Materials''' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Composite materials are a material group whose properties are of great importance for electrical contacts that are used in switching devices for higher | |

| + | electrical currents. | ||

| − | + | Those used in electrical contacts are heterogeneous materials, composed of two or more uniformly dispersed components, in which the largest volume portion consists of a metal. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Those used in electrical contacts are heterogeneous materials composed of two | ||

| − | or more uniformly dispersed components in which the largest volume portion | ||

| − | consists of a metal | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The properties of composite materials are determined mainly independent from each other by the properties of their individual components. Therefore it is, for example, possible to combine the high melting point and arc erosion resistance of tungsten with the low melting and good electrical conductivity of copper or the high conductivity of silver with the weld resistant metalloid graphite. <xr id="fig:Powder metallurgical manufacturing of composite materials (schematic)"/> shows the schematic manufacturing processes from powder blending to contact material. Three basic process variations are typically applied: | |

| − | blending to contact material. Three basic process variations are typically | ||

| − | applied: | ||

*Sintering without liquid phase (Press-Sinter-Repress, PSR) | *Sintering without liquid phase (Press-Sinter-Repress, PSR) | ||

| Line 71: | Line 42: | ||

*Infiltration (Press-Sinter-Infiltrate, PSI) | *Infiltration (Press-Sinter-Infiltrate, PSI) | ||

| − | + | <figure id="fig:Powder metallurgical manufacturing of composite materials (schematic)"> | |

| − | + | [[File:Powder metallurgical manufacturing of composite materials (schematic).jpg|thumb|<caption>Powder-metallurgical manufacturing of composite materials (schematic) T<sub>s</sub> = Melting point of the lower melting component)</caption>]] | |

| − | + | </figure> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ( | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | During ''sintering without a liquid phase'' (left side of schematic), the powder mix is first densified by pressing, then undergoes a heat treatment (sintering) and eventually is re-pressed again to further increase the density. The sintering atmosphere depends on the material components and later application; a vacuum is used for example for the low gas content material Cu/Cr. This process is used for individual contact parts and also termed press-sinter-repress (PSR). For materials with high silver content, the starting point before pressing is mostly a large block (or billet) which is then, after sintering, hot extruded into wire, rod or strip form. The extrusion further increases the density of these composite materials and contributes to higher arc erosion resistance. Materials such as Ag/Ni, Ag/MeO and Ag/C are typically produced by this process. | |

| − | |||

| − | composite material. To ensure the shape stability during the sintering process it | + | ''Sintering with liquid phase'' has the advantage of shorter process times due to the accelerated diffusion and also results in near-theoretical densities of the composite material. To ensure the shape stability during the sintering process, it |

is however necessary to limit the volume content of the liquid phase material. | is however necessary to limit the volume content of the liquid phase material. | ||

| − | As opposed to the liquid phase sintering which has limited use for electrical | + | As opposed to the liquid phase sintering, which has limited use for electrical contact manufacturing, the ''Infiltration process'' as shown on the right side of the schematic, has a broad practical range of applications. In this process the powder of the higher melting component, sometimes also as a powder mix with a small amount of the second material, is pressed into parts. Then, right after sintering, the porous skeleton is infiltrated with liquid metal of the second material. The fill-up process of the pores happens through capillary forces. This process reaches, after the infiltration, near-theoretical density without subsequent pressing and is widely used for Ag- and Cu-refractory contacts. For Ag/W or Ag/WC contacts, controlling the amount or excess on the bottom side of the contact of the infiltration metal Ag, results in contact tips that can be easily attached to their carriers by resistance welding. For larger Cu/W contacts, additional machining is often used to obtain the final shape of the contact component. |

| − | contact manufacturing, the Infiltration process as shown on the right side of the | ||

| − | schematic has a broad practical range of applications. In this process the | ||

| − | powder of the higher melting component sometimes also as a powder mix with | ||

| − | a small amount of the second material is pressed into parts | ||

| − | the porous skeleton is infiltrated with liquid metal of the second material. The | ||

| − | |||

| − | after the infiltration near-theoretical density without subsequent pressing and is | ||

| − | widely used for Ag- and Cu-refractory contacts. For Ag/W or Ag/WC contacts, | ||

| − | controlling the amount or excess on the bottom side of the contact of the | ||

| − | infiltration metal Ag results in contact tips that can be easily attached to their | ||

| − | carriers by resistance welding. For larger Cu/W contacts additional machining is | ||

| − | often used to obtain the final shape of the contact component. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Gold Based Materials== | |

| − | + | Pure Gold is besides Platinum the chemically most stable of all precious metals. In its pure form, it is not very suitable for use as a contact material in electromechanical devices because of its tendency to stick and cold-weld at even low contact forces. In addition, it is not hard or strong enough to resist mechanical wear and exhibits high material losses under electrical arcing loads. This limits its use in form of thin electroplated or vacuum deposited layers. | |

| − | + | Main Article: [[Gold Based Materials| Gold Based Materials]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Platinum Metal Based Materials== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The platinum group metals include the elements Pt, Pd, Rh, Ru, Ir and Os ([[Platinum_Metal_Based_Materials|Table 1]]<!--(Table 2.6)-->). For electrical contacts, platinum and palladium have practical significance as base alloy materials and ruthenium and iridium are used as alloying components. Pt and Pd have similar corrosion resistance as gold but due to their catalytical properties, they tend to polymerize adsorbed organic vapors on contact surfaces. During frictional movement between contact surfaces, the polymerized compounds known as “brown powder” are formed, which can lead to a significant increase in contact resistance. Therefore Pt and Pd are typically used as alloys and are rather not used in their pure form for electrical contact applications. | |

| − | |||

| − | which | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Main Article: [[Platinum Metal Based Materials| Platinum Metal Based Materials]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Silver Based Materials== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Main Article: [[Silver Based Materials| Silver Based Materials]] | |

| − | + | ==Tungsten and Molybdenum Based Materials== | |

| − | + | Main Article: [[Tungsten and Molybdenum Based Materials| Tungsten and Molybdenum Based Materials]] | |

| − | + | ==Contact Materials for Vacuum Switches== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The low gas content contact materials are developed for the use in vacuum switching devices. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Main Article: [[Contact Materials for Vacuum Switches| Contact Materials for Vacuum Switches]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Vinaricky, E.(Hrsg.): Elektrische Kontakte, Werkstoffe und Anwendungen. | |

| − | + | Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg etc. 2002 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Lindmayer, M.: Schaltgeräte-Grundlagen, Aufbau, Wirkungsweise. | |

| − | + | Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokio, 1987 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Rau, G.: Metallische Verbundwerkstoffe. Werkstofftechnische | |

| − | + | Verlagsgesellschaft, Karlsruhe 1977 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Schreiner, H.: Pulvermetallurgie elektrischer Kontakte. Springer-Verlag | |

| − | + | Berlin, Göttingen, Heidelberg, 1964 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Hansen. M.; Anderko, K.: Constitution of Binary Alloys. New York: | |

| − | + | Mc Graw-Hill, 1958 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Shunk, F.A.: Constitution of Binary Alloy. 2 Suppl. New York; Mc Graw-Hill, 1969 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Edelmetall-Taschenbuch. ( Herausgeber Degussa AG, Frankfurt a. M.), | |

| − | + | Heidelberg, Hüthig-Verlag, 1995 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Rau, G.: Elektrische Kontakte-Werkstoffe und Technologie. Eigenverlag G. Rau | |

| − | + | GmbH & Co., Pforzheim, 1984 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Heraeus, W. C.: Werkstoffdaten. Eigenverlag W.C. Heraeus, Hanau, 1978 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Linde, J.O.: Elektrische Widerstandseigenschaften der verdünnten Legierungen | |

| − | + | des Kupfers, Silbers und Goldes. Lund: Hakan Ohlsson, 1938 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Engineers Relay Handbook, RSIA, 2006 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Großmann, H. Saeger, K. E.; Vinaricky, E.: Gold and Gold Alloys in Electrical | |

| − | + | Engineering. in: Gold, Progress in Chemistry, Biochemistry and Technology. John | |

| − | + | Wiley & Sons, Chichester etc, (1999) 199-236 | |

| − | + | Gehlert, B.: Edelmetall-Legierungen für elektrische Kontakte. | |

| − | + | Metall 61 (2007) H. 6, 374-379 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Aldinger, F.; Schnabl, R.: Edelmetallarme Kontakte für kleine Ströme. | |

| − | + | Metall 37 (1983) 23-29 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Bischoff, A.; Aldinger, F.: Einfluss geringer Zusätze auf die mechanischen | |

| − | + | Eigenschaften von Au-Ag-Pd-Legierungen. Metall 36 (1982) 752-765 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Wise, E.M.: Palladium, Recovery, Properties and Uses. New York, London: | |

| − | + | Academic Press 1968 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Savitskii, E.M.; Polyakova, V.P.; Tylina, M.A.: Palladium Alloys, Primary Sources. | |

| − | + | New York: Publishers 1969 | |

| − | + | Gehlert, B.: Lebensdaueruntersuchungen von Edelmetall Kontaktwerkstoff- | |

| − | + | Kombinationen für Schleifringübertrager. VDE-Fachbericht 61, (2005) 95-100 | |

| − | + | Holzapfel,C.: Verschweiß und elektrische Eigenschaften von | |

| + | Schleifringübertragern. VDE-Fachbericht 67 (2011) 111-120 | ||

| − | + | Schnabl, R.; Gehlert, B.: Lebensdauerprüfungen von Edelmetall- | |

| − | + | Schleifkontaktwerkstoffen für Gleichstrom Kleinmotoren. | |

| − | + | Feinwerktechnik & Messtechnik (1984) 8, 389-393 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Kobayashi, T.; Koibuchi, K.; Sawa, K.; Endo, K.; Hagino, H.: A Study of Lifetime | |

| − | + | of Au-plated Slip-Ring and AgPd Brush System for Power Supply. | |

| − | + | th Proc. 24 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 537-542 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Harmsen, U.; Saeger K.E.: Über das Entfestigungsverhalten von Silber | |

| − | + | verschiedener Reinheiten. Metall 28 (1974) 683-686 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Behrens, V.; Michal, R.; Minkenberg, J.N.; Saeger, K.E.: Abbrand und | |

| + | Kontaktwiderstandsverhalten von Kontaktwerkstoffen auf Basis von Silber- | ||

| + | Nickel. e.& i. 107. Jg. (1990), 2, 72-77 | ||

| − | + | Behrens, V.: Silber/Nickel und Silber/Grafit- zwei Spezialisten auf dem Gebiet | |

| + | der Kontaktwerkstoffe. Metall 61 (2007) H.6, 380-384 | ||

| − | + | Rieder, W.: Silber / Metalloxyd-Werkstoffe für elektrische Kontakte, | |

| − | + | VDE - Fachbericht 42 (1991) 65-81 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Harmsen,U.: Die innere Oxidation von AgCd-Legierungen unter | |

| − | + | Sauerstoffdruck. | |

| − | + | Metall 25 (1991), H.2, 133-137 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Muravjeva, E.M.; Povoloskaja, M.D.: Verbundwerkstoffe Silber-Zinkoxid und | |

| − | + | Silber-Zinnoxid, hergestellt durch Oxidationsglühen. | |

| − | + | Elektrotechnika 3 (1965) 37-39 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Behrens, V.; Honig Th.; Kraus, A.; Michal, R.; Saeger, K.-E.; Schmidberger, R.; | |

| − | + | Staneff, Th.: Eine neue Generation von AgSnO<sub>2</sub> -Kontaktwerkstoffen. | |

| − | + | VDE-Fachbericht 44, (1993) 99-114 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Braumann, P.; Lang, J.: Kontaktverhalten von Ag-Metalloxiden für den Bereich | |

| − | + | hoher Ströme. VDE-Fachbericht 42, (1991) 89-94 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Hauner, F.; Jeannot, D.; Mc Neilly, U.; Pinard, J.: Advanced AgSnO Contact 2 | |

| − | + | th Materials for High Current Contactors. Proc. 20 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact | |

| − | + | Phenom., Stockholm 2000, 193-198 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Wintz, J.-L.; Hardy, S.; Bourda, C.: Influence on the Electrical Performances of | |

| − | + | Assembly Process, Supports Materials and Production Means for AgSnO<sub>2</sub> . | |

| − | + | Proc.24<sub>th</sub> Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 75-81 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Behrens, V.; Honig, Th.; Kraus, A.; Michal, R.: Schalteigenschaften von | |

| − | + | verschiedenen Silber-Zinnoxidwerkstoffen in Kfz-Relais. VDE-Fachbericht 51 | |

| − | + | (1997) 51-57 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Schöpf, Th.: Silber/Zinnoxid und andere Silber-Metalloxidwerkstoffe in | |

| − | + | Netzrelais. VDE-Fachbericht 51 (1997) 41-50 | |

| − | + | Schöpf, Th.; Behrens, V.; Honig, Th.; Kraus, A.: Development of Silver Zinc | |

| − | + | th Oxide for General-Purpose Relays. Proc. 20 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, | |

| − | + | Stockholm 2000, 187-192 | |

| − | + | Braumann, P.; Koffler, A.: Einfluss von Herstellverfahren, Metalloxidgehalt und | |

| − | + | Wirkzusätzen auf das Schaltverhalten von Ag/SnO in Relais. 2 | |

| − | + | VDE-Fachbericht 59, (2003) 133-142 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Kempf, B.; Braumann, P.; Böhm, C.; Fischer-Bühner, J.: Silber-Zinnoxid- | |

| + | Werkstoffe: Herstellverfahren und Eigenschaften. Metall 61(2007) H. 6, 404-408 | ||

| − | + | Lutz, O.; Behrens, V.; Finkbeiner, M.; Honig, T.; Späth, D.: Ag/CdO-Ersatz in | |

| − | + | Lichtschaltern. VDE-Fachbericht 61, (2005) 165-173 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Lutz, O.; Behrens, V.; Wasserbäch, W.; Franz, S.; Honig, Th.; Späth, | |

| − | + | D.; Heinrich, J.: Improved Silver/Tin Oxide Contact Materials for Automotive | |

| − | + | th Applications. Proc.24 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, | |

| − | + | 88-93 | |

| − | + | Leung, C.; Behrens, V.: A Review of Ag/SnO Contact Materials and Arc Erosion. 2 | |

| − | + | th Proc.24 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 82-87 | |

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Chen, Z.K.; Witter, G.J.: Comparison in Performance for Silver–Tin–Indium | |

| − | + | Oxide Materials Made by Internal Oxidation and Powder Metallurgy. | |

| − | + | th Proc. 55 IEEE Holm Conf. on Electrical Contacts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, | |

| + | (2009) 167 – 176 | ||

| − | + | Roehberg, J.; Honig, Th.; Witulski, N.; Finkbeiner, M.; Behrens, V.: Performance | |

| − | of | + | of Different Silver/Tin Oxide Contact Materials for Applications in Low Voltage |

| − | + | th Circuit Breakers. Proc. 55 IEEE Holm Conf. on Electrical Contacts, Vancouver, | |

| + | BC, Canada, (2009) 187 – 194 | ||

| − | + | Muetzel, T.; Braumann, P.; Niederreuther, R.: Temperature Rise Behavior of | |

| − | + | th Ag/SnO Contact Materials for Contactor Applications. Proc. 55 IEEE Holm 2 | |

| − | + | Conf. on Electrical Contacts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, (2009) 200 – 205 | |

| − | + | Lutz, O. et al.: Silber/Zinnoxid – Kontaktwerkstoffe auf Basis der Inneren | |

| − | + | Oxidation fuer AC – und DC – Anwendungen. | |

| − | + | VDE Fachbericht 65 (2009) 167 – 176 | |

| − | + | Harmsen, U.; Meyer, C.L.: Mechanische Eigenschaften stranggepresster Silber- | |

| − | + | Graphit-Verbundwerkstoffe. Metall 21 (1967), 731-733 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Behrens, V.: Mahle, E.; Michal, R.; Saeger, K.E.: An Advanced Silver/Graphite | |

| + | th Contact Material Based on Graphite Fibre. Proc. 16 Int. Conf. on Electr. | ||

| + | Contacts, Loghborough 1992, 185-189 | ||

| − | + | Schröder, K.-H.; Schulz, E.-D.: Über den Einfluss des Herstellungsverfahrens | |

| − | + | th auf das Schaltverhalten von Kontaktwerkstoffen der Energietechnik. Proc. 7 Int. | |

| − | + | Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Paris 1974, 38-45 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Mützel, T.: Niederreuther, R.: Kontaktwerkstoffe für Hochleistungsanwendungen. | |

| − | + | VDE-Bericht 67 (2011) 103-110 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Lambert, C.; Cambon, G.: The Influence of Manufacturing Conditions and | |

| − | + | Metalurgical Characteristics on the Electrical Behaviour of Silver-Graphite | |

| − | + | th Contact Materials. Proc. 9 Int. Conf.on Electr. Contacts, | |

| + | Chicago 1978, 401-406 | ||

| − | + | Vinaricky, E.: Grundsätzliche Untersuchungen zum Abbrand- und | |

| − | + | Schweißverhalten von Ag/C-Kontaktwerkstoffen. VDE-Fachbericht 47 (1995) | |

| − | + | 159-169 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Agte, C.; Vacek, J.: Wolfram und Molybdän. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 1959 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Keil, A.; Meyer, C.-L.: Der Einfluß des Faserverlaufes auf die elektrische | |

| − | + | Verschleißfestigkeit von Wolfram-Kontakten. ETZ 72, (1951) 343-346 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Slade, P. G.: Electric Contacts for Power Interruption. A Review. Proc. 19 Int. | |

| − | + | Conf. on Electric Contact Phenom. Nuremberg (Germany) 1998, 239-245 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Slade, P. G.: Variations in Contact Resistance Resulting from Oxide Formation | |

| − | + | and Decomposition in AgW and Ag-WC-C Contacts Passing Steady Currents | |

| − | + | for Long Time Periods. IEEE Trans. Components, Hybrids and Manuf. Technol. | |

| − | + | CHMT-9,1 (1986) 3-16 | |

| − | + | Slade, P. G.: Effect of the Electric Arc and the Ambient Air on the Contact | |

| − | + | Resistance of Silver, Tungsten and Silver-Tungsten Contacts. | |

| − | + | J.Appl.Phys. 47, 8 (1976) 3438-3443 | |

| − | + | Lindmayer, M.; Roth, M.: Contact Resistance and Arc-Erosion of W-Ag and | |

| − | + | WC-Ag. IEEE Trans components, Hybrids and Manuf. Technol. | |

| − | + | CHMT-2, 1 (1979) 70-75 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Leung, C.-H.; Kim, H.J.: A Comparison of Ag/W, Ag/WC and Ag/Mo Electrical | |

| − | + | Contacts. IEEE Trans. Components, Hybrids, Manuf. Technol., | |

| − | + | Vol. CHMT-7, 1 (1984) 69-75 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Allen, S.E.; Streicher, E.: The Effect of Microstructure on the Electrical | |

| − | + | th Performance of Ag-WC-C Contact Materials. Proc. 44 IEEE Holm Conf. on Electr. | |

| − | of | + | Contacts, Arlington, VA, USA (1998), 276-285 |

| − | |||

| − | + | Haufe, W.; Reichel, W.; Schreiner H.: Abbrand verschiedener W/Cu-Sinter- | |

| + | Tränkwerkstoffe an Luft bei hohen Strömen. Z. Metallkd. 63 (1972) 651-654 | ||

| − | + | Althaus, B.; Vinaricky, E.: Das Abbrandverhalten verschieden hergestellter | |

| + | Wolfram-Kupfer-Verbundwerkstoffe im Hochstromlichtbogen. | ||

| + | Metall 22 (1968) 697-701 | ||

| − | + | Gessinger, G.H.; Melton, K.N.: Burn-off Behaviour of WCu Contact Materials in an | |

| − | + | Electric Arc. Powder Metall. Int. 9 (1977) 67-72 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Magnusson, M.: Abbrandverhalten und Rißbildung bei WCu-Tränkwerkstoffen | |

| − | + | unterschiedlicher Wolframteilchengröße. ETZ-A 98 (1977) 681-683 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Heitzinger, F.; Kippenberg, H.; Saeger, K.E.; Schröder, K.H.: Contact Materials for | |

| − | + | Vacuum Switching Devices. Proc. XVth ISDEIV, Darmstadt 1992, 273-278 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Grill, R.; Müller, F.: Verbundwerkstoffe auf Wolframbasis für | |

| + | Hochspannungsschaltgeräte. Metall 61 (2007) H. 6, 390-393 | ||

| − | + | Slade, P.: G.: The Vacuum Interrupter- Theory; Design; and Application. CRC | |

| − | + | Press, Boca Raton, FL (USA), 2008 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Frey, P.; Klink, N.; Saeger, K.E.: Untersuchungen zum Abreißstromverhalten von | |

| − | + | Kontaktwerkstoffen für Vakuumschütze. Metall 38 (1984) 647-651 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Frey, P.; Klink, N.; Michal, R.; Saeger, K.E.: Metallurgical Aspects of Contact | |

| − | + | Materials for Vacuum Switching Devices. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sc. 17, (1989) 743- | |

| − | + | 740 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Slade, P.: Advances in Material Development for High Power Vacuum Interrupter | |

| − | + | th Contacts. Proc.16 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact Phenom., | |

| − | + | Loughborough 1992,1-10 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Behrens, V.; Honig, Th.; Kraus, A.; Allen, S.: Comparison of Different Contact | |

| + | th Materials for Low Voltage Vacuum Applications. Proc.19 Int. Conf. on Electr. | ||

| + | Contact Phenom., Nuremberg 1998, 247-251 | ||

| − | + | Rolle, S.; Lietz, A.; Amft, D.; Hauner, F.: CuCr Contact Material for Low Voltage | |

| + | th Vacuum Contactors. Proc. 20 int. Conf. on Electr. Contact. Phenom. Stockholm | ||

| + | 2000, 179-186 | ||

| − | + | Kippenberg, H.: CrCu as a Contact Material for Vacuum Interrupters. | |

| + | th Proc.13 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact Phenom. Lausanne 1986, 140-144 | ||

| − | + | Hauner, F.; Müller, R.; Tiefel, R.: CuCr für Vakuumschaltgeräte- | |

| + | Herstellungsverfahren, Eigenschaften und Anwendung. | ||

| + | Metall 61 (2007) H. 6, 385-389 | ||

| − | + | Manufacturing Equipment for Semi-Finished Materials | |

| + | (Bild) | ||

| − | + | [[de:Kontaktwerkstoffe_für_die_Elektrotechnik]] | |

Latest revision as of 12:54, 26 January 2023

The contact parts are important components in switching devices. They have to maintain their function from the new state until the end of the functional life of the devices.

The requirements on contacts are rather broad. Besides typical contact properties such as

- High arc erosion resistance

- High resistance against welding

- Low contact resistance

- Good arc moving properties

- Good arc extinguishing capability

They have to exhibit physical, mechanical and chemical properties like high electrical and thermal conductivity, high hardness, high corrosion resistance etc. and besides this, should have good mechanical workability and also be suitable for good weld and brazing attachment to contact carriers. In addition they must be made from environmentally friendly materials.

Materials suited for use as electrical contacts can be divided into the following groups based on their composition and metallurgical structure:

- Pure metals

- Alloys

- Composite materials

Pure metals

Within this group, silver has the greatest importance for switching devices in the higher energy technology. Other precious metals such as gold and platinum are only used in applications for the information technology in the form of thin surface layers. As a nonprecious metal, tungsten is used for some special applications such as, for example, automotive horn contacts. In some rarer cases, pure copper is used, but mainly paired to a silver-based contact material.

Alloys

Besides these few pure metals, a larger number of alloy materials made by melt technology are available for the use as contacts. An alloy is characterized by the fact, that its components are completely or partially soluble in each other in the solid state. Phase diagrams for multiple metal compositions show the number and type of the crystal structure as a function of the temperature and composition of the alloying components.

They indicate the boundaries of liquid and solid phases and define the parameters of solidification. Alloying allows to improve the properties of one material at the cost of changing them for the second material. As an example, the hardness of a base metal may be increased while at the same time the electrical conductivity decreases with even small additions of the second alloying component.

Composite Materials

Composite materials are a material group whose properties are of great importance for electrical contacts that are used in switching devices for higher electrical currents.

Those used in electrical contacts are heterogeneous materials, composed of two or more uniformly dispersed components, in which the largest volume portion consists of a metal.

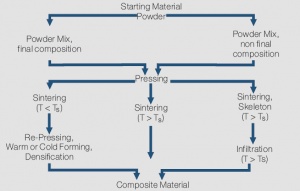

The properties of composite materials are determined mainly independent from each other by the properties of their individual components. Therefore it is, for example, possible to combine the high melting point and arc erosion resistance of tungsten with the low melting and good electrical conductivity of copper or the high conductivity of silver with the weld resistant metalloid graphite. Figure 1 shows the schematic manufacturing processes from powder blending to contact material. Three basic process variations are typically applied:

- Sintering without liquid phase (Press-Sinter-Repress, PSR)

- Sintering with liquid phase

- Infiltration (Press-Sinter-Infiltrate, PSI)

During sintering without a liquid phase (left side of schematic), the powder mix is first densified by pressing, then undergoes a heat treatment (sintering) and eventually is re-pressed again to further increase the density. The sintering atmosphere depends on the material components and later application; a vacuum is used for example for the low gas content material Cu/Cr. This process is used for individual contact parts and also termed press-sinter-repress (PSR). For materials with high silver content, the starting point before pressing is mostly a large block (or billet) which is then, after sintering, hot extruded into wire, rod or strip form. The extrusion further increases the density of these composite materials and contributes to higher arc erosion resistance. Materials such as Ag/Ni, Ag/MeO and Ag/C are typically produced by this process.

Sintering with liquid phase has the advantage of shorter process times due to the accelerated diffusion and also results in near-theoretical densities of the composite material. To ensure the shape stability during the sintering process, it is however necessary to limit the volume content of the liquid phase material.

As opposed to the liquid phase sintering, which has limited use for electrical contact manufacturing, the Infiltration process as shown on the right side of the schematic, has a broad practical range of applications. In this process the powder of the higher melting component, sometimes also as a powder mix with a small amount of the second material, is pressed into parts. Then, right after sintering, the porous skeleton is infiltrated with liquid metal of the second material. The fill-up process of the pores happens through capillary forces. This process reaches, after the infiltration, near-theoretical density without subsequent pressing and is widely used for Ag- and Cu-refractory contacts. For Ag/W or Ag/WC contacts, controlling the amount or excess on the bottom side of the contact of the infiltration metal Ag, results in contact tips that can be easily attached to their carriers by resistance welding. For larger Cu/W contacts, additional machining is often used to obtain the final shape of the contact component.

Contents

Gold Based Materials

Pure Gold is besides Platinum the chemically most stable of all precious metals. In its pure form, it is not very suitable for use as a contact material in electromechanical devices because of its tendency to stick and cold-weld at even low contact forces. In addition, it is not hard or strong enough to resist mechanical wear and exhibits high material losses under electrical arcing loads. This limits its use in form of thin electroplated or vacuum deposited layers.

Main Article: Gold Based Materials

Platinum Metal Based Materials

The platinum group metals include the elements Pt, Pd, Rh, Ru, Ir and Os (Table 1). For electrical contacts, platinum and palladium have practical significance as base alloy materials and ruthenium and iridium are used as alloying components. Pt and Pd have similar corrosion resistance as gold but due to their catalytical properties, they tend to polymerize adsorbed organic vapors on contact surfaces. During frictional movement between contact surfaces, the polymerized compounds known as “brown powder” are formed, which can lead to a significant increase in contact resistance. Therefore Pt and Pd are typically used as alloys and are rather not used in their pure form for electrical contact applications.

Main Article: Platinum Metal Based Materials

Silver Based Materials

Main Article: Silver Based Materials

Tungsten and Molybdenum Based Materials

Main Article: Tungsten and Molybdenum Based Materials

Contact Materials for Vacuum Switches

The low gas content contact materials are developed for the use in vacuum switching devices.

Main Article: Contact Materials for Vacuum Switches

References

Vinaricky, E.(Hrsg.): Elektrische Kontakte, Werkstoffe und Anwendungen. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg etc. 2002

Lindmayer, M.: Schaltgeräte-Grundlagen, Aufbau, Wirkungsweise. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Tokio, 1987

Rau, G.: Metallische Verbundwerkstoffe. Werkstofftechnische Verlagsgesellschaft, Karlsruhe 1977

Schreiner, H.: Pulvermetallurgie elektrischer Kontakte. Springer-Verlag Berlin, Göttingen, Heidelberg, 1964

Hansen. M.; Anderko, K.: Constitution of Binary Alloys. New York: Mc Graw-Hill, 1958

Shunk, F.A.: Constitution of Binary Alloy. 2 Suppl. New York; Mc Graw-Hill, 1969

Edelmetall-Taschenbuch. ( Herausgeber Degussa AG, Frankfurt a. M.), Heidelberg, Hüthig-Verlag, 1995

Rau, G.: Elektrische Kontakte-Werkstoffe und Technologie. Eigenverlag G. Rau GmbH & Co., Pforzheim, 1984

Heraeus, W. C.: Werkstoffdaten. Eigenverlag W.C. Heraeus, Hanau, 1978

Linde, J.O.: Elektrische Widerstandseigenschaften der verdünnten Legierungen des Kupfers, Silbers und Goldes. Lund: Hakan Ohlsson, 1938

Engineers Relay Handbook, RSIA, 2006

Großmann, H. Saeger, K. E.; Vinaricky, E.: Gold and Gold Alloys in Electrical Engineering. in: Gold, Progress in Chemistry, Biochemistry and Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester etc, (1999) 199-236

Gehlert, B.: Edelmetall-Legierungen für elektrische Kontakte. Metall 61 (2007) H. 6, 374-379

Aldinger, F.; Schnabl, R.: Edelmetallarme Kontakte für kleine Ströme. Metall 37 (1983) 23-29

Bischoff, A.; Aldinger, F.: Einfluss geringer Zusätze auf die mechanischen Eigenschaften von Au-Ag-Pd-Legierungen. Metall 36 (1982) 752-765

Wise, E.M.: Palladium, Recovery, Properties and Uses. New York, London: Academic Press 1968

Savitskii, E.M.; Polyakova, V.P.; Tylina, M.A.: Palladium Alloys, Primary Sources. New York: Publishers 1969

Gehlert, B.: Lebensdaueruntersuchungen von Edelmetall Kontaktwerkstoff- Kombinationen für Schleifringübertrager. VDE-Fachbericht 61, (2005) 95-100

Holzapfel,C.: Verschweiß und elektrische Eigenschaften von Schleifringübertragern. VDE-Fachbericht 67 (2011) 111-120

Schnabl, R.; Gehlert, B.: Lebensdauerprüfungen von Edelmetall- Schleifkontaktwerkstoffen für Gleichstrom Kleinmotoren. Feinwerktechnik & Messtechnik (1984) 8, 389-393

Kobayashi, T.; Koibuchi, K.; Sawa, K.; Endo, K.; Hagino, H.: A Study of Lifetime of Au-plated Slip-Ring and AgPd Brush System for Power Supply. th Proc. 24 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 537-542

Harmsen, U.; Saeger K.E.: Über das Entfestigungsverhalten von Silber verschiedener Reinheiten. Metall 28 (1974) 683-686

Behrens, V.; Michal, R.; Minkenberg, J.N.; Saeger, K.E.: Abbrand und Kontaktwiderstandsverhalten von Kontaktwerkstoffen auf Basis von Silber- Nickel. e.& i. 107. Jg. (1990), 2, 72-77

Behrens, V.: Silber/Nickel und Silber/Grafit- zwei Spezialisten auf dem Gebiet der Kontaktwerkstoffe. Metall 61 (2007) H.6, 380-384

Rieder, W.: Silber / Metalloxyd-Werkstoffe für elektrische Kontakte, VDE - Fachbericht 42 (1991) 65-81

Harmsen,U.: Die innere Oxidation von AgCd-Legierungen unter Sauerstoffdruck. Metall 25 (1991), H.2, 133-137

Muravjeva, E.M.; Povoloskaja, M.D.: Verbundwerkstoffe Silber-Zinkoxid und Silber-Zinnoxid, hergestellt durch Oxidationsglühen. Elektrotechnika 3 (1965) 37-39

Behrens, V.; Honig Th.; Kraus, A.; Michal, R.; Saeger, K.-E.; Schmidberger, R.; Staneff, Th.: Eine neue Generation von AgSnO2 -Kontaktwerkstoffen. VDE-Fachbericht 44, (1993) 99-114

Braumann, P.; Lang, J.: Kontaktverhalten von Ag-Metalloxiden für den Bereich hoher Ströme. VDE-Fachbericht 42, (1991) 89-94

Hauner, F.; Jeannot, D.; Mc Neilly, U.; Pinard, J.: Advanced AgSnO Contact 2 th Materials for High Current Contactors. Proc. 20 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact Phenom., Stockholm 2000, 193-198

Wintz, J.-L.; Hardy, S.; Bourda, C.: Influence on the Electrical Performances of Assembly Process, Supports Materials and Production Means for AgSnO2 . Proc.24th Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 75-81

Behrens, V.; Honig, Th.; Kraus, A.; Michal, R.: Schalteigenschaften von verschiedenen Silber-Zinnoxidwerkstoffen in Kfz-Relais. VDE-Fachbericht 51 (1997) 51-57

Schöpf, Th.: Silber/Zinnoxid und andere Silber-Metalloxidwerkstoffe in Netzrelais. VDE-Fachbericht 51 (1997) 41-50

Schöpf, Th.; Behrens, V.; Honig, Th.; Kraus, A.: Development of Silver Zinc th Oxide for General-Purpose Relays. Proc. 20 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Stockholm 2000, 187-192

Braumann, P.; Koffler, A.: Einfluss von Herstellverfahren, Metalloxidgehalt und Wirkzusätzen auf das Schaltverhalten von Ag/SnO in Relais. 2 VDE-Fachbericht 59, (2003) 133-142

Kempf, B.; Braumann, P.; Böhm, C.; Fischer-Bühner, J.: Silber-Zinnoxid- Werkstoffe: Herstellverfahren und Eigenschaften. Metall 61(2007) H. 6, 404-408

Lutz, O.; Behrens, V.; Finkbeiner, M.; Honig, T.; Späth, D.: Ag/CdO-Ersatz in Lichtschaltern. VDE-Fachbericht 61, (2005) 165-173

Lutz, O.; Behrens, V.; Wasserbäch, W.; Franz, S.; Honig, Th.; Späth, D.; Heinrich, J.: Improved Silver/Tin Oxide Contact Materials for Automotive th Applications. Proc.24 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 88-93

Leung, C.; Behrens, V.: A Review of Ag/SnO Contact Materials and Arc Erosion. 2 th Proc.24 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Saint Malo, France 2008, 82-87

Chen, Z.K.; Witter, G.J.: Comparison in Performance for Silver–Tin–Indium Oxide Materials Made by Internal Oxidation and Powder Metallurgy. th Proc. 55 IEEE Holm Conf. on Electrical Contacts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, (2009) 167 – 176

Roehberg, J.; Honig, Th.; Witulski, N.; Finkbeiner, M.; Behrens, V.: Performance of Different Silver/Tin Oxide Contact Materials for Applications in Low Voltage th Circuit Breakers. Proc. 55 IEEE Holm Conf. on Electrical Contacts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, (2009) 187 – 194

Muetzel, T.; Braumann, P.; Niederreuther, R.: Temperature Rise Behavior of th Ag/SnO Contact Materials for Contactor Applications. Proc. 55 IEEE Holm 2 Conf. on Electrical Contacts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, (2009) 200 – 205

Lutz, O. et al.: Silber/Zinnoxid – Kontaktwerkstoffe auf Basis der Inneren Oxidation fuer AC – und DC – Anwendungen. VDE Fachbericht 65 (2009) 167 – 176

Harmsen, U.; Meyer, C.L.: Mechanische Eigenschaften stranggepresster Silber- Graphit-Verbundwerkstoffe. Metall 21 (1967), 731-733

Behrens, V.: Mahle, E.; Michal, R.; Saeger, K.E.: An Advanced Silver/Graphite th Contact Material Based on Graphite Fibre. Proc. 16 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Loghborough 1992, 185-189

Schröder, K.-H.; Schulz, E.-D.: Über den Einfluss des Herstellungsverfahrens th auf das Schaltverhalten von Kontaktwerkstoffen der Energietechnik. Proc. 7 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Paris 1974, 38-45

Mützel, T.: Niederreuther, R.: Kontaktwerkstoffe für Hochleistungsanwendungen. VDE-Bericht 67 (2011) 103-110

Lambert, C.; Cambon, G.: The Influence of Manufacturing Conditions and Metalurgical Characteristics on the Electrical Behaviour of Silver-Graphite th Contact Materials. Proc. 9 Int. Conf.on Electr. Contacts, Chicago 1978, 401-406

Vinaricky, E.: Grundsätzliche Untersuchungen zum Abbrand- und Schweißverhalten von Ag/C-Kontaktwerkstoffen. VDE-Fachbericht 47 (1995) 159-169

Agte, C.; Vacek, J.: Wolfram und Molybdän. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 1959

Keil, A.; Meyer, C.-L.: Der Einfluß des Faserverlaufes auf die elektrische Verschleißfestigkeit von Wolfram-Kontakten. ETZ 72, (1951) 343-346

Slade, P. G.: Electric Contacts for Power Interruption. A Review. Proc. 19 Int. Conf. on Electric Contact Phenom. Nuremberg (Germany) 1998, 239-245

Slade, P. G.: Variations in Contact Resistance Resulting from Oxide Formation and Decomposition in AgW and Ag-WC-C Contacts Passing Steady Currents for Long Time Periods. IEEE Trans. Components, Hybrids and Manuf. Technol. CHMT-9,1 (1986) 3-16

Slade, P. G.: Effect of the Electric Arc and the Ambient Air on the Contact Resistance of Silver, Tungsten and Silver-Tungsten Contacts. J.Appl.Phys. 47, 8 (1976) 3438-3443

Lindmayer, M.; Roth, M.: Contact Resistance and Arc-Erosion of W-Ag and WC-Ag. IEEE Trans components, Hybrids and Manuf. Technol. CHMT-2, 1 (1979) 70-75

Leung, C.-H.; Kim, H.J.: A Comparison of Ag/W, Ag/WC and Ag/Mo Electrical Contacts. IEEE Trans. Components, Hybrids, Manuf. Technol., Vol. CHMT-7, 1 (1984) 69-75

Allen, S.E.; Streicher, E.: The Effect of Microstructure on the Electrical th Performance of Ag-WC-C Contact Materials. Proc. 44 IEEE Holm Conf. on Electr. Contacts, Arlington, VA, USA (1998), 276-285

Haufe, W.; Reichel, W.; Schreiner H.: Abbrand verschiedener W/Cu-Sinter- Tränkwerkstoffe an Luft bei hohen Strömen. Z. Metallkd. 63 (1972) 651-654

Althaus, B.; Vinaricky, E.: Das Abbrandverhalten verschieden hergestellter Wolfram-Kupfer-Verbundwerkstoffe im Hochstromlichtbogen. Metall 22 (1968) 697-701

Gessinger, G.H.; Melton, K.N.: Burn-off Behaviour of WCu Contact Materials in an Electric Arc. Powder Metall. Int. 9 (1977) 67-72

Magnusson, M.: Abbrandverhalten und Rißbildung bei WCu-Tränkwerkstoffen unterschiedlicher Wolframteilchengröße. ETZ-A 98 (1977) 681-683

Heitzinger, F.; Kippenberg, H.; Saeger, K.E.; Schröder, K.H.: Contact Materials for Vacuum Switching Devices. Proc. XVth ISDEIV, Darmstadt 1992, 273-278

Grill, R.; Müller, F.: Verbundwerkstoffe auf Wolframbasis für Hochspannungsschaltgeräte. Metall 61 (2007) H. 6, 390-393

Slade, P.: G.: The Vacuum Interrupter- Theory; Design; and Application. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL (USA), 2008

Frey, P.; Klink, N.; Saeger, K.E.: Untersuchungen zum Abreißstromverhalten von Kontaktwerkstoffen für Vakuumschütze. Metall 38 (1984) 647-651

Frey, P.; Klink, N.; Michal, R.; Saeger, K.E.: Metallurgical Aspects of Contact Materials for Vacuum Switching Devices. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sc. 17, (1989) 743- 740

Slade, P.: Advances in Material Development for High Power Vacuum Interrupter th Contacts. Proc.16 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact Phenom., Loughborough 1992,1-10

Behrens, V.; Honig, Th.; Kraus, A.; Allen, S.: Comparison of Different Contact th Materials for Low Voltage Vacuum Applications. Proc.19 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact Phenom., Nuremberg 1998, 247-251

Rolle, S.; Lietz, A.; Amft, D.; Hauner, F.: CuCr Contact Material for Low Voltage th Vacuum Contactors. Proc. 20 int. Conf. on Electr. Contact. Phenom. Stockholm 2000, 179-186

Kippenberg, H.: CrCu as a Contact Material for Vacuum Interrupters. th Proc.13 Int. Conf. on Electr. Contact Phenom. Lausanne 1986, 140-144

Hauner, F.; Müller, R.; Tiefel, R.: CuCr für Vakuumschaltgeräte- Herstellungsverfahren, Eigenschaften und Anwendung. Metall 61 (2007) H. 6, 385-389

Manufacturing Equipment for Semi-Finished Materials (Bild)